Thursday, February 01, 2007

Don't Look Here!

Are stolen military IDs going on the black market? Is the NSA going underground to fix Fort Gordon’s security problems? The Garden City isn’t as sleepy as you think.By Corey Pein

The purse was designed to honor the Dukes of Hazzard. A couple of weeks ago it lay unattended on the floorboard of a white Hyundai SUV, which was parked outside the Augusta Ice Sports Center.

Sometime between 7 and 8:30 p.m., a thief broke the passenger-side window and made off with the purse. Inside were a cell phone, a key ring, some credit cards and identification.

A broken window, a stolen purse, a lost ID. For most people, this would be a headache.

For those in the military and intelligence business — which is quite a lot of people around here — it could be a serious problem, one that affects everybody.

The theft of that military ID was one more potential hole in the security of Fort Gordon and the National Security Agency offices there. The man who called police about the theft of his wife’s purse, the report indicated, worked for the Navy in a secure intelligence facility.

Such thefts are common, judging by Richmond County Sheriff’s Office reports. Rarely does a week go by without at least one military-issued card reported lost or stolen, usually out of a vehicle. At least three were reported stolen last week.

No doubt many such thefts are run-of-the-mill acts of petty crooks looking for stereos or cash who wouldn’t recognize the value of a military ID. But what concerns the Department of Defense are the professional underworld types who know what can be done with a ticket into a secure area.

A July 2005 military intelligence report, first obtained by journalist William Arkin, reveals official concerns about a growing black market in stolen and counterfeit military IDs.

The report, prepared by the Pentagon’s Counterintelligence Field Activity, a classified agency that conducts surveillance within the United States, says, “The mere possession of a stolen card could, in fact, pose a security risk.”

Many locals are aware that the National Security Agency — so secret that the government didn’t admit its existence for several decades — has a major presence at Fort Gordon.

But fewer people know the nature of what the NSA is doing here. Augusta is the agency’s main listening post for the Middle East.

Just down Gordon Highway, intelligence analysts — your neighbors — are eavesdropping on conversations happening in Iraq, Iran and elsewhere in the region. They’re looking for information of use to the planners and fighters of America’s wars.

It’s the kind of work that can change the course of history. That’s why it’s secret. And that’s why any security holes at the base — even seemingly minor ones — can endanger the lives of soldiers abroad and civilians at home.

Considering the nature of some missions that go on at Fort Gordon, you might expect it to be among the most secure places in the world, right up there with the Central Intelligence Agency’s headquarters in Langley, Virginia.

It’s not. At least not for the time being.

Many buildings are aging and unsuitable for sensitive operations. The personnel make occasional mistakes, as human beings are bound to do. And the security policies imposed from on high don’t always improve the situation.

For example, when the Pentagon decided in 1999 to modernize and standardize military IDs throughout the bureaucracy, it hoped to strengthen security. The decision may have inadvertently weakened it.

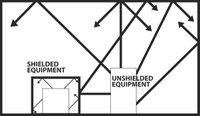

One principle embraced by hackers and security experts alike is the importance of having multiple levels of security. The Common Access Card now issued to military personnel forsakes layered fail-safes in favor of a single piece of plastic.

The card includes an abundance of digital information: the holder’s name, Social Security Number, date of birth, rank, blood type and other information, including e-mail and computer passwords.

According to an NSA assessment cited in the 2005 counterintelligence report, the cards are vulnerable to hacking. Some weaknesses “have yet to be mitigated.”

Fort Gordon’s security problems have been an open secret for years. Soldiers sometimes laugh knowingly when you bring up the issue.

The base’s problems begin with the land around it. The military reservation has a 43-mile perimeter, most of which is forested and borders public roads.

As the home of the Army’s signal corps, as well as thousands of soldiers and their families, the base itself was not designed to host a super-secret spy station.

Nor does the base’s culture, which people who’ve trained and worked there describe as relatively laid-back, seem to have kept pace with the increasing sensitivity of its operations.

John Young, who runs the intelligence Web site cryptome.org, recounted a 2002 conversation with an anonymous cryptological officer stationed at Fort Gordon: “Security measures taken at GRSOC are very lax, even in this post-Sept. 11 world,” the officer told Young. “A sailor newly arrived, not wanting to wait in a holding unit until issued a security clearance, was able to find a way into working in a SCIF.”

SCIF stands for sensitive compartmented information facility, which denotes an area that should be very much off-limits to people who don’t have the right security clearances. GRSOC is the acronym for the Georgia Regional Security Operations Center, a joint-service facility established by the NSA and housed at Fort Gordon.

Inside accounts like this are supported by outside observation.

After the 9/11 attacks, when just about everything of any importance in the United States seemed to be under armed guard, Fort Gordon stepped up its security procedures. There were long lines on the road leading onto the base as guards searched cars and checked IDs.

Meanwhile, about 200 yards away from a guard booth, people were sneaking onto the base through the woods. Granted, they were allowed to be on base. They were, apparently, employees at Eisenhower Medical Center who decided to park their cars nearby and walk a quarter-mile to avoid the three-hour delays at the checkpoint.

“We haven’t had anybody do that in a while,” says Barry Wood, director of business and public affairs at the National Science Center Foundation, located off Gordon Highway. He remembers noticing the telltale Fort Gordon stickers on cars in the parking lot outside his building. “Really,” Wood says, “there was nothing much to it.”

That may be true, but consider the implications. For a moment, think like a spy.

If it’s that easy to slip onto base during one of the most paranoid moments in American history, how hard would it be for a determined person with malicious intent on an ordinary day of the week? Especially if he looked like he was supposed to be there — if he had, say, a military ID card.

Of course, just because someone can sneak on base doesn’t mean he can stroll right into a sensitive compartmented information facility. The really important secret stuff is hidden.

There is another “but” here: A well-equipped spy wouldn’t necessarily have to get inside his target. Turning the NSA’s own techniques against it, all he would have to do is get close. Which turns out to be pretty easy at Fort Gordon.

“If a spy can get within 300 feet of where classified material is handled, he owns it,” says James Atkinson, who calls himself the Spyhunter. “I mean, he owns it big time.”

Atkinson used to work for the NSA and, he says, “other organizations I don’t talk about.” Now, as the president and senior engineer of Granite Island Group, a Massachusetts-based security consulting firm, he’s still immersed in the world of intelligence, counterintelligence and, one can presume, counter-anti-counterintelligence.

He has clients in business and in government. They often fail to recognize security holes that to him seem big enough to steer a tank through.

Technology creates some of the most critical vulnerabilities. In the modern world, people are like walking radio towers, always broadcasting. Most of us don’t realize this. Just about everything that’s electronic can be intercepted at a distance. (Your cell phone can even be turned on remotely and used as a listening device, without your knowledge.)

Your phone, your television and your computer all give off electromagnetic radiation with distinct frequencies. With the right equipment, it’s possible to separate those signals and know what’s being said over the phone, shown on the screen or processed by the computer. The same applies to the machines the NSA relies on, even though they are specially shielded.

Though it used to be thought that only governments could afford to produce sophisticated interception gear, technological improvements make covert eavesdropping easier all the time. For example, in 2003, a Cambridge University professor demonstrated that he could piece together the information on a computer monitor based on the dim reflections the monitors made on the wall, even through curtains or blinds. And that’s not the only way to spy from a distance.

“If I can get close enough, I can read everything that the cryptographic equipment does,” Atkinson says. “Let’s say we deliberately put a wireless camera into the President’s office. The advertised range is 50 feet. If a spy is very dedicated to what he’s doing and has a significant amount of money, he can extend the distance of his reception by one-thousand fold.”

Thus the camera’s supposed 50-foot signal could be picked up eight-and-a-half miles away. “It’s simple electronics,” Atkinson says. “This is historical, not secret.”

Many of Atkinson’s most interesting stories are, like that one, hypothetical. At least, he phrases them hypothetically.

“We can go to the White House a week after Christmas, when everybody gets back from vacation,” he says, “and the security people are going bonkers, trying to cleanse the White House of all those Bluetooth headsets and Crackberries people just picked up for Christmas.” Wireless gadgets are particularly insecure.

Last year the Metro Spirit reported that the Navy contingent at Fort Gordon purchased hundreds of iPods for language training. Might they be vulnerable to eavesdropping?

“If they have an iPod at work [and] that iPod has a transmitter on it, they’re transmitting room audio,” Atkinson says.

Most iPods now come equipped with transmitters, so you can send your music to an FM radio and play it over the speakers. If a gadget doesn’t already have a transmitter in it, Atkinson says, one could be covertly installed while the owner is at the gym or church.

As a matter of fact, last weekend, a Navy issued iPod was stolen from a young man’s car parked on Broad Street. His work phone number can be tracked to Fort Gordon and what appears to be an intelligence group.

The NSA already knows all of these vulnerabilities. Their engineers invented many of the spy techniques that might be used against them. And the agency takes measures to guard its equipment from remote eavesdropping. They call it “information assurance,” and they take it very seriously.

Those measures, however, may not be enough.

These buildings were not made for the task. Given the agency’s expanding mission, they are now overcrowded and stretched to capacity. And they are much closer to the curb than the 300-foot danger zone described by Atkinson.

“The exposed position of the main operations facility on Fort Gordon leaves the facility at risk to threats from potential adversaries,” according to a Pentagon budget document drafted in February of 2006.

“None of the facilities meet the minimum standards or requirements for Antiterrorism Force Protection, DOD operation facilities, Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) or life-safety,” the document says.

Back Hall, a large sensitive compartmented information facility originally used for classrooms, has only a “50-foot setback from Chamberlain Avenue, which is an unrestricted major thoroughfare with no entry control points other than inside the main entrance.” Two other buildings, the headquarters of NSA Georgia and an annex, were converted, respectively, from a cafeteria and a mailroom. A building used for language training was originally a barracks. These facilities, the document says, were “not designed or constructed to be an intelligence center” and have exceeded their practical lifetimes.

There is a reason the NSA — which rarely reveals anything about itself — publicly disclosed all this troubling information. It wanted the money to build a new facility.

Ask and ye shall receive.

Work will commence this year on a $340-million, 525,000-square-foot new NSA facility at Fort Gordon. It’s called project Sweet Tea, and it’s the biggest thing going up anywhere near Augusta, though you wouldn’t know it by the dearth of publicity.

The project had been in the works for years. The contract wasn’t announced until after the Metro Spirit began making inquiries in December, though it was scheduled to have been awarded as early as September.

The new buildings are supposed to fix all those security problems with the current structures. Sweet Tea includes a new shredder facility and antenna farm, along with such amenities as a workout room, nursing areas, a mini shopping center, a credit union, an 800-seat cafeteria and lots of parking spaces. One aspect of Sweet Tea hasn’t yet been reported, and that is, the literal depth of the project.

The construction contract went to Phelps/Kiewit Joint Venture out of Virginia. Both companies bring expertise to the project. Hensel Phelps Construction won the rebuilding contract for the Pentagon after 9/11.

Kiewit is an interesting choice. One of the company’s specialties is tunneling.

The company did some work on Nevada’s Yucca Mountain, the controversial nuclear waste dump. Back during the Cold War, Kiewit built many of the nuclear missile silos still scattered across the Midwestern United States.

So what, you ask?

It looks like NSA Georgia is going underground. Other American intelligence agencies already have, not to mention the North Koreans and the Iranians.

Not only would tunneling solve, pretty definitively, the NSA’s setback problem, it would guard against nuclear and electromagnetic attack (which works something like how George Clooney’s gang shut down the power in Las Vegas in “Ocean’s Eleven”).

The new and improved Georgia Regional Security Operations Center is supposed to be occupied by December 2011.

That means five years of living with the current, not-up-to-code Fort Gordon facilities.

An NSA spokesperson declined to discuss the setback problem on the record. The agency did respond to certain questions in writing:

“Q: How will you handle security while building the new facility? Will everyone [who works on the building] have to be cleared?

“A: According to an NSAG spokesperson, contract security personnel will be assigned 24/7 for the protection of the site, access control, and badge issuance for contractor personnel. All persons requiring access within the boundaries of a government project site or restricted access area must comply with all security requirements. One primary requirement is that all persons must be U.S. citizens. Depending on the information obtained, access may be denied.”

Atkinson says that, as usual, these measures — and the military’s standard security procedures — don’t go far enough. He knows how he would handle security during construction, if he were in charge.

“First of all, you build [the facility] in a remote area, way out in the middle of a corn field somewhere. And before you start breaking ground, you build a double berm on the outside, so somebody who’s driving by cannot see what’s going on,” he says.

The outer berm should be covered with trees and vegetation. The inner berm should be patrolled. There should be chain-link fences with barbed wire inside and outside the berms. Bright lighting is important. The idea, he says, is to “create a no man’s land.”

The buildings should be no closer to the berm than 1,000 feet, Atkinson says, to “make sure there’s no way in hell anyone can get closer than 300 feet to the building. A good rule is four times that distance.”

There should be surveillance cameras all over the place, both visible and covert, as well as multiple entrances.

“You create a type of maze, so if someone approaches in a semi truck at 60 miles per hour, they cannot get to the building,” Atkinson says. “You have multiple guards, and they’re in the houses seven/twenty-four, and there’s absolutely no reason for them to leave the guardhouse.”

It’s an open question whether procedures at Fort Gordon during the construction of Sweet Tea will be as strict as Atkinson suggests.

***

“Perhaps you can recall your initial impression upon entering an NSA facility. Like most people, you probably noticed the elaborate physical security safeguards — fences, concrete barriers, Security Protective Officers, identification badges, etc. While these measures provide a substantial degree of protection for the information housed within our buildings, they represent only a portion of the overall Agency security program. In fact, vast amounts of information leave our facilities daily in the minds of NSA personnel, and this is where our greatest vulnerability lies. … Agency personnel may become potential targets for hostile intelligence efforts.”

— From an NSA Security Guidelines Handbook posted by Atkinson

As ever, the biggest problem is people. People are people. People screw up, even when they’re well trained.

As ever, the biggest problem is people. People are people. People screw up, even when they’re well trained. The screening process for security clearances, which take months to obtain and involve background checks and extensive interviews, is supposed to eliminate people prone to winding up compromising situations.

The process doesn’t always work.

For instance, in 2005, Said Mutazz, a young Air Force enlisted man who worked in intelligence at Fort Gordon, reportedly as a linguist, was charged with murder along with another man, Walter Geter. Police said it was a botched drug deal.

Mutazz’s attorney, Pete Theodocion, says the case will have to be retried. Among other problems with the state’s case, Mutazz wasn’t read his Miranda rights.

Theodocion says the Air Force helped Mutazz out with his bond, but eventually kicked him out after he tested positive for marijuana.

If someone obtains a clearance and later becomes a security risk, they are supposed to lose that clearance or even, like Mutazz, get the boot.

Clearances can be revoked for seemingly minor infractions — like going too far into debt, for instance. The reasoning is that someone with financial problems is more liable to accept work as a double agent.

Smoking dope is obviously verboten. As would be murder.

But mistakes are forgivable. Fort Gordon’s public affairs says the loss of an ID card does not affect an individual’s security clearance, “unless it is done intentionally for profit.”

That happens, apparently. The 2005 Counterintelligence Field Activity report mentioned early in this story says investigators suspect some Defense Department personnel of illegally obtaining and selling military ID materials.

There’s no indication that such mercenary subterfuge has taken place at Fort Gordon. But, to a determined adversary, that doesn’t really matter. He doesn’t need to buy a key to get through the gate. All he has to do is find the holes in the fence.

Where to start?

Where else? Google.

The military has removed much information that used to be publicly available from the Internet since 9/11, but apparently without rhyme or reason.

For example, the Web site for Total Information Awareness, a program designed to compile massive dossiers of data on pretty much every American, was taken down after the controversial program’s existence was revealed in the newspapers. It seemed like a public relations move.

But other information that might actually be of use to an adversary, such as intelligence personnel’s names and job titles, is still available online.

A quick search turns up a PowerPoint presentation designed to accompany a course on “information assurance” given at Fort Gordon.

“There is NO security without Physical Security!” the briefing warns.

Among other things, it warns against plugging unauthorized devices into classified computers (officially issued iPods may be “authorized,” but they could always be compromised). It urges officers to log out of their computers when they get up and leave, even for a short time. And so on.

The briefing also contains the names of the instructors, some of whom are in the phone book and live off base, where there are no guards, no berms and no barbed wire.

Even if the military removed all potentially compromising information from its own Web sites — and that may be impossible — it can’t always control what its personnel post elsewhere.

The people who serve in intelligence tend to be bright. But they are also, oftentimes, young — which is to say, they can be stupid.

The NSA security handbook says, in the section titled “answering questions about your employment,” that “you may say that you are a linguist, if necessary. However, you should not indicate the specific language(s) with which you are involved.”

Now, you don’t have to be in Augusta long to meet fresh young Americans hanging around a bar, demonstrating an impressive fluency in Arabic, perhaps in an attempt to impress a member of the opposite sex.

A clever spy might follow these people out of the bar, see what car they get into, and take it from there.

Or, a clever spy, knowing that many intelligence analysts are trained at the Defense Language Institute in Monterey, California, might look to see who in Augusta has attended that school.

This hypothetical spy might be happy to find dozens of potential targets who have posted quite a bit of personal information on social networking and dating Web sites.

If the MySpace site says “male, single, 26, Gemini” residing at “Fort Gordon” and lists his job as “intelligence analyst” employed by the “Navy,” it doesn’t take a James Bond to figure out who he’s working for.

What can you do? People are people.

---From the Feb. 1 issue of the Augusta, Ga. Metro Spirit.

1. Military ID/CAC card. There is this myth that the chip on the CAC card holds all this private data. This is not true. The only data on the chip besides a public encryption key is the information actually printed on the card. It just so happens your SSN, blood type, etc. is also printed on the card.

Secondly, a stolen access card will not grant anyone access to any secure facility. To gain access, one typically needs a pin or code to get in the front door, and then other codes to get into secure areas within the building.

Thirdly, the TEMPEST technique the self-described NSA man (very doubtful he actually worked for the NSA) has been common knowledge for decades and secure facilities are designed to prevent such emmissions.

I could go on, but what's the point?

http://www.EveryStepYouTake.org

http://www.prosefights.org/nmlegal/fbifoia/mueller/mueller.htm#becknell

What's disappointing is that this information was made so easily available. If the vulnerabilities of a military installation were made so readily available to a journalist for an independent paper, then what has been made available to the true enemies out there?

I agree it should be taken as a warning to those on the base up there to acknowledge the risks and take action by getting the security standards up to par.

Well I dont know if its a threat to security, its more of a wakeup call and the only way to make security stronger is to post the holes to the public in order to garner enough attention to close them. report it right away lol, that is the intention and we still live in a nation of free speech so its all good. The article breaks no laws as from what I have researched, Anonymous is just trying to play up the "I am powerful and someone with a secret job" thing, he in reality is most likely a private.

In addition to the false assumptions and sloppy research, I also take exception to the fact that the author quotes hearsay and people who have no connection with the facility as if they were informed sources. In particular, your "SpyHunter" seems to be dubious at best. Why not just have a Hollywood screenwriter come up with "hypothetical" scenarios for cracking national security? It would have had about the same credibility as this "source."

There was one area where this article comes close to the truth: the most important part of security is the human element. One thing that we're taught, above all, to protect ourselves and our mission is to be discreet. No, the fact that we do what we do is not classified. But we don't need to go around telling everyone that Fort Gordon is the NSA's "main listening post for the Middle East." Because doing so makes us a pretty attractive target.

So, thank you, Metro Spirit and Mr. Pein. Thank you for advancing your careers and selling newspapers by negating our efforts to protect ourselves and our mission -- all the while pretending to care about "holes" in national security!

With regard to the post, I read about 1/3 of it, but browse through enough to see theres a good point trying to be made. Also, human behavior can ultimately defeat any precautions put up to protect information. One scenario could go like this. Someone leaves a USB drive in a conspicuous place that could be found by the targetted person, people tend to be curious and pick it up to see whats inside. (on the new U3 flashdrives you don't even have to open the file because it could autorun itself and do what it needs)

From: a concerned college student

Luke

<< Home

Metro Spirit national security blog

Metro Spirit national security blog